Inside the Sensory Bubble

An essential way to think about crafting explanations for others

I ended the last post on The Baseline Problem with a key quote from Ed Yong’s book “An Immense World”:

Earth teems with sights and textures, sounds and vibrations, smells and tastes, electric and magnetic fields. But every animal can only tap into a small fraction of reality’s fullness. Each is enclosed within its own unique sensory bubble, perceiving but a tiny sliver of an immense world.

Yong’s sensory bubble, which is based on the work of German biologist Jakob von Uexküll (1864–1944), who called it “Umwelt,” is a foundational part of the science of explanation. Here’s why:

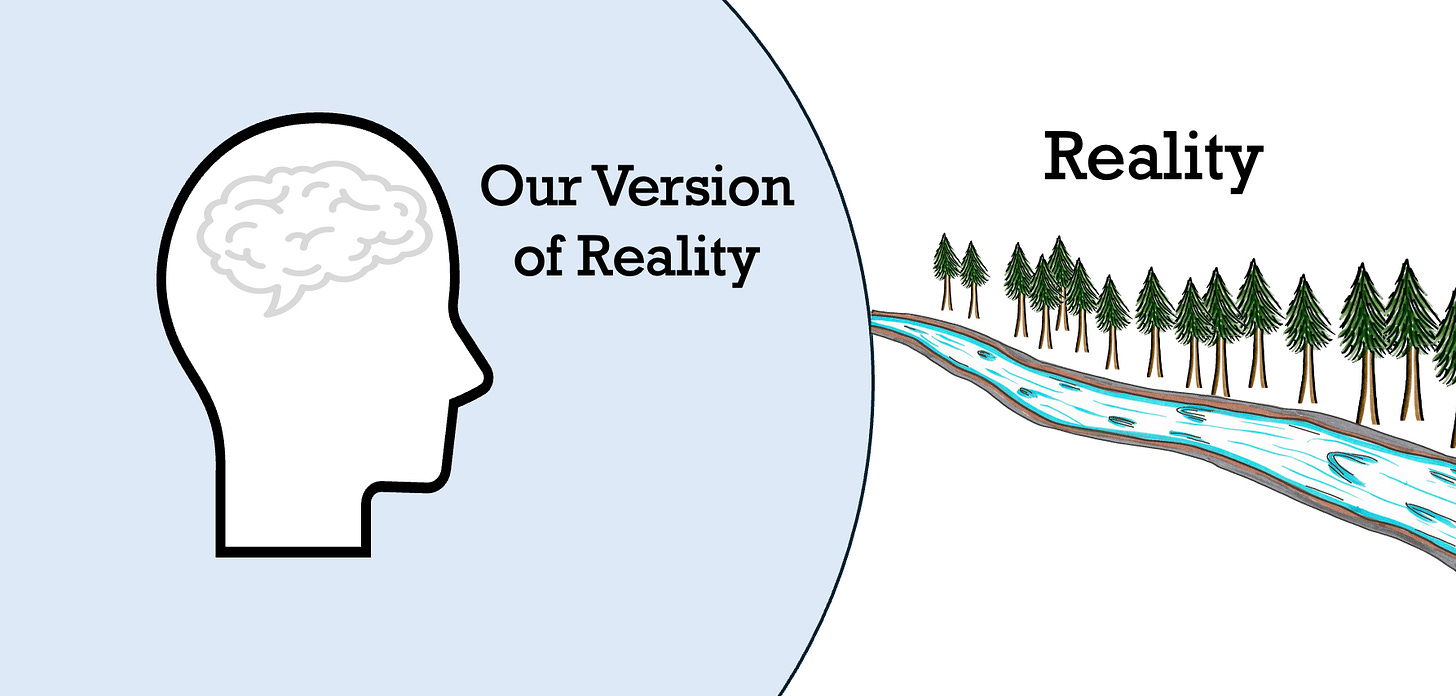

We all live in sensory bubbles that we cannot escape. Everything we know and do happens inside the bubble and is subject to our biology, experience, and knowledge.

The wall of the bubble acts as an interface to the “real” world outside of it. It’s not a physical boundary, but an always-on process that constantly translates reality from our senses into something useful to our minds. And only a fraction of “true” reality, what our senses can perceive, can make it through the wall.

I think of it like this: Whatever “true” reality is made of, we initially experience it as information. A rose has shape, color, smell, and taste that can be represented with data. The data lives outside the bubble, in true reality. When we experience a rose, that information comes into the bubble, and needs to be transformed into something we can use.

So the brain quickly processes the rose. Without thinking about it, we recognize what it is and how it works. We make predictions about the scent and apply existing knowledge that serves as a shortcut. This process happens constantly in the background and represents our version of reality. Information comes into the bubble, and we process it immediately.

Is the rose real? Yes. But our experience is not the genuine article, but one version among millions.

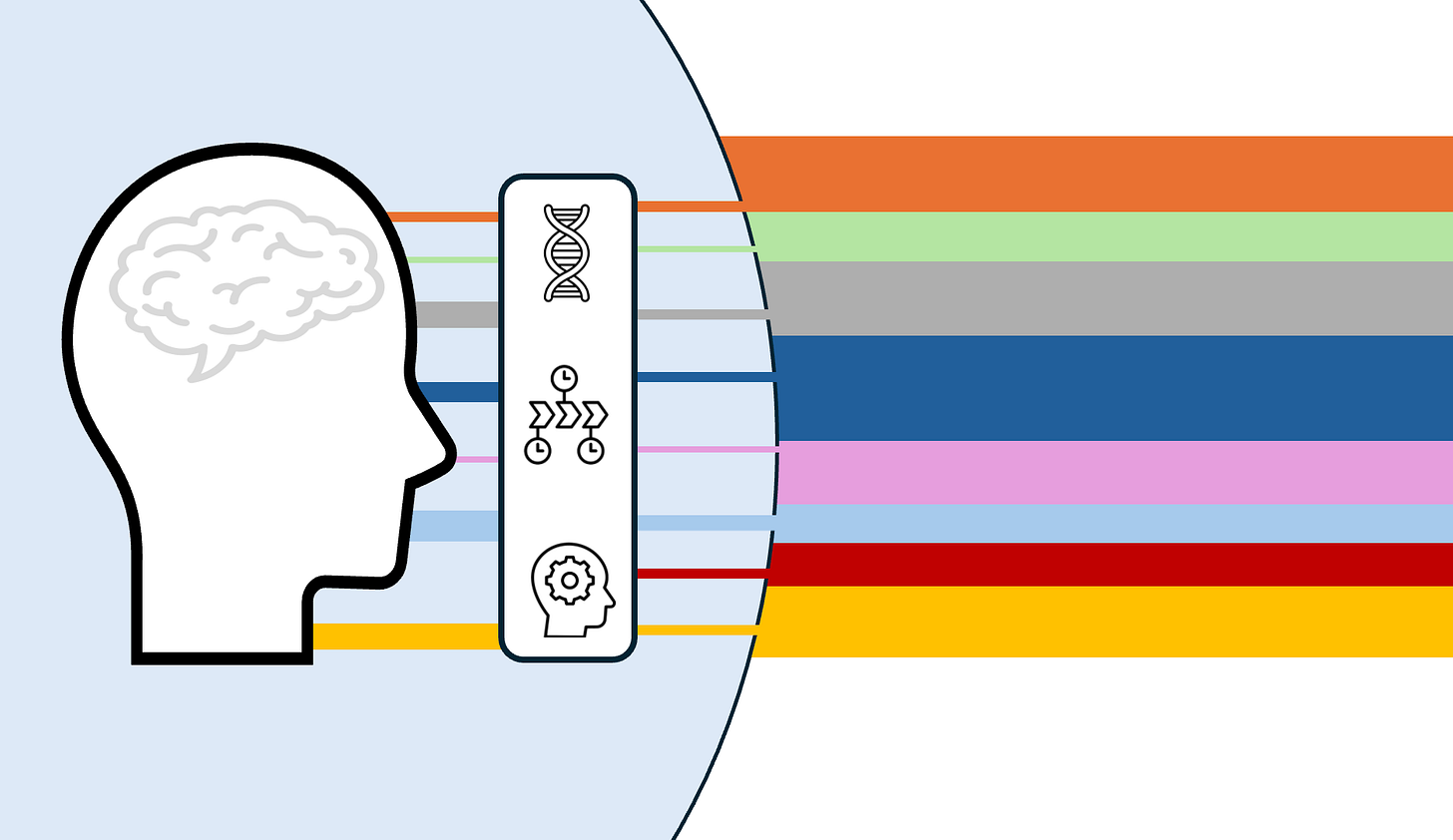

Among the Human Bubbles

While human bubbles are mostly alike in terms of the interface, each of our bubbles is unique on the inside. We all have lived experiences, learning styles, accumulated knowledge, and personalities that make us different. When new information arrives in the bubble, we differ in what we do with it. We assign different forms of meaning or relevance. We pay attention to different aspects of ideas.

The exact same rose can be experienced in very different ways, depending on the person. A rose expert can notice things the novice misses.

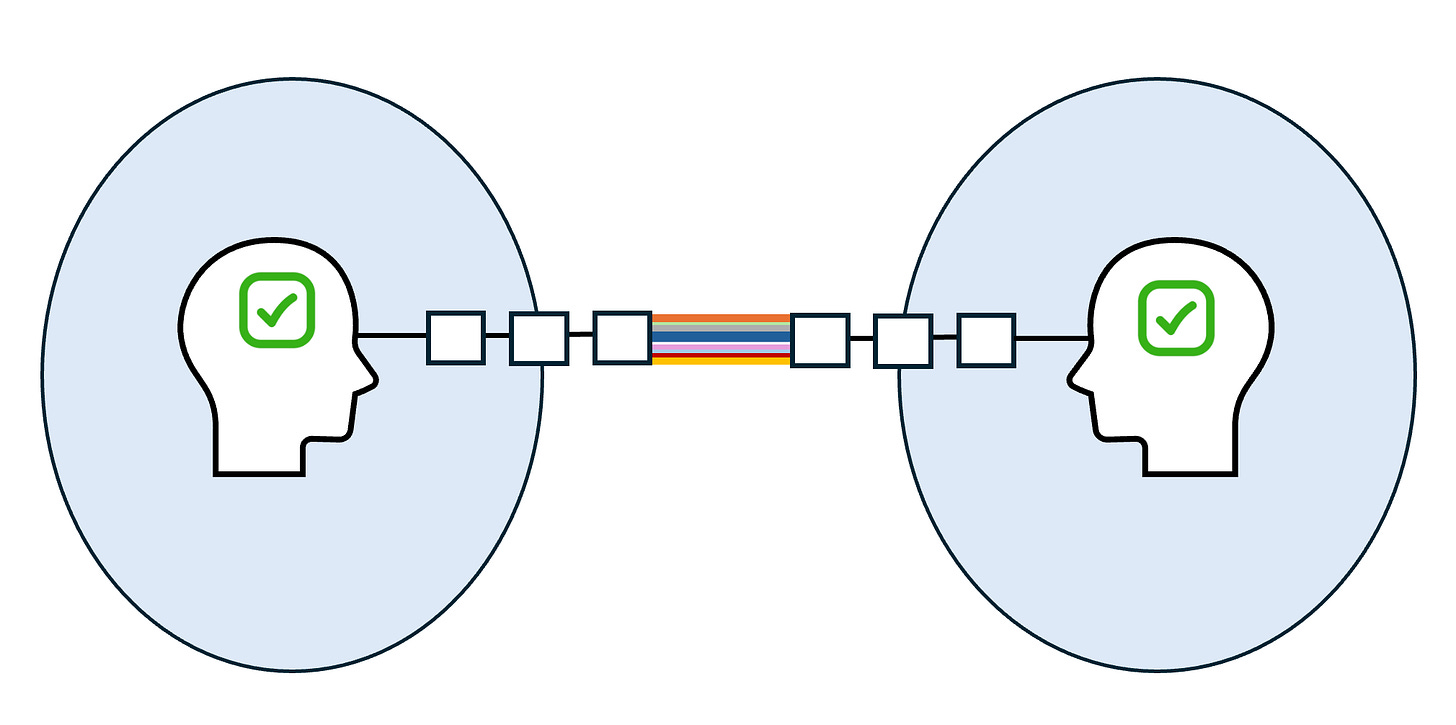

This is why the bubble metaphor is useful for thinking about explanation and communication. When we explain ideas, they must travel between bubbles in a form that’s useful. That’s a real challenge, because we can’t know what it’s like in someone else’s bubble. We have to assume that every bubble is unique. What can we do?

The Mind in the Bubble

Within our respective bubbles, there is a brain that functions similarly across people. Thanks to cognitive science, we now have a grasp on how information from outside the bubble becomes knowledge within it.

Imagine a doctor telling you, “Eat more fiber because it can lower cholesterol.” A few weeks later, you’re on a high fiber diet and proud of your progress. Your doctor’s words became knowledge in your mind. How did that happen? Why those words and not others?

Human brains process information in predictable ways. Cognitive science has identified the patterns we use to filter and evaluate information as it comes into the bubble. When your doctor spoke, you automatically paid attention, grasped the gist, assigned meaning, and encoded it for later use. Remembering to get milk on the way home? That didn’t make the cut.

The key for explainers is to understand those patterns so we can design explanations to fit them. When we want information to become knowledge, we can think about each step of the pattern and how to optimize. We can ask: what ingredients must be present for this to work inside someone’s bubble?

For example, attention is an essential step. Without it, the idea dies quickly. For your explanation to succeed, you’ll need to consider how to get and hold attention. This is a part of cognitive science that we’ll explore later.

Bubble as a Tool

I will be referring to sensory bubbles from now on. The bubble metaphor allows us to think about three situations in context:

Our bubbles: what we experience as reality

True reality: the world outside of our bubble

Other people’s bubbles: how our communication works in other bubbles

The driving question, starting now, is: how can I explain so that information is useful inside someone else’s bubble?

We now know the basic ingredients that help turn information into knowledge across diverse bubbles. We understand the power of context, attention, encoding, and more. And by thinking in terms of bubbles, we have a way to consider what will work for each person in our audience.

Next: A Brief Explainer Video

Next week, I’ll share a brief post with a video that brings this idea to life. I hope you’ll watch it and let me know what you think.

If You Enjoyed This Post

Please consider hitting the ♡ button below (it helps others find this post)

I’d love to hear from you. Leave a comment, and we can chat.

Know someone who would enjoy this? This post is public, so feel free to share.

Lee, interesting as always. Here's what popped (excuse the bubble joke) into my mind. 1. Is the bubble flexible and can it expand or contract. 2. What if, instead of a bubble, I conjured up a walled fortress. New information can come it because I open the gates or new information can come in because something breaks the gate down from the outside.